Intro

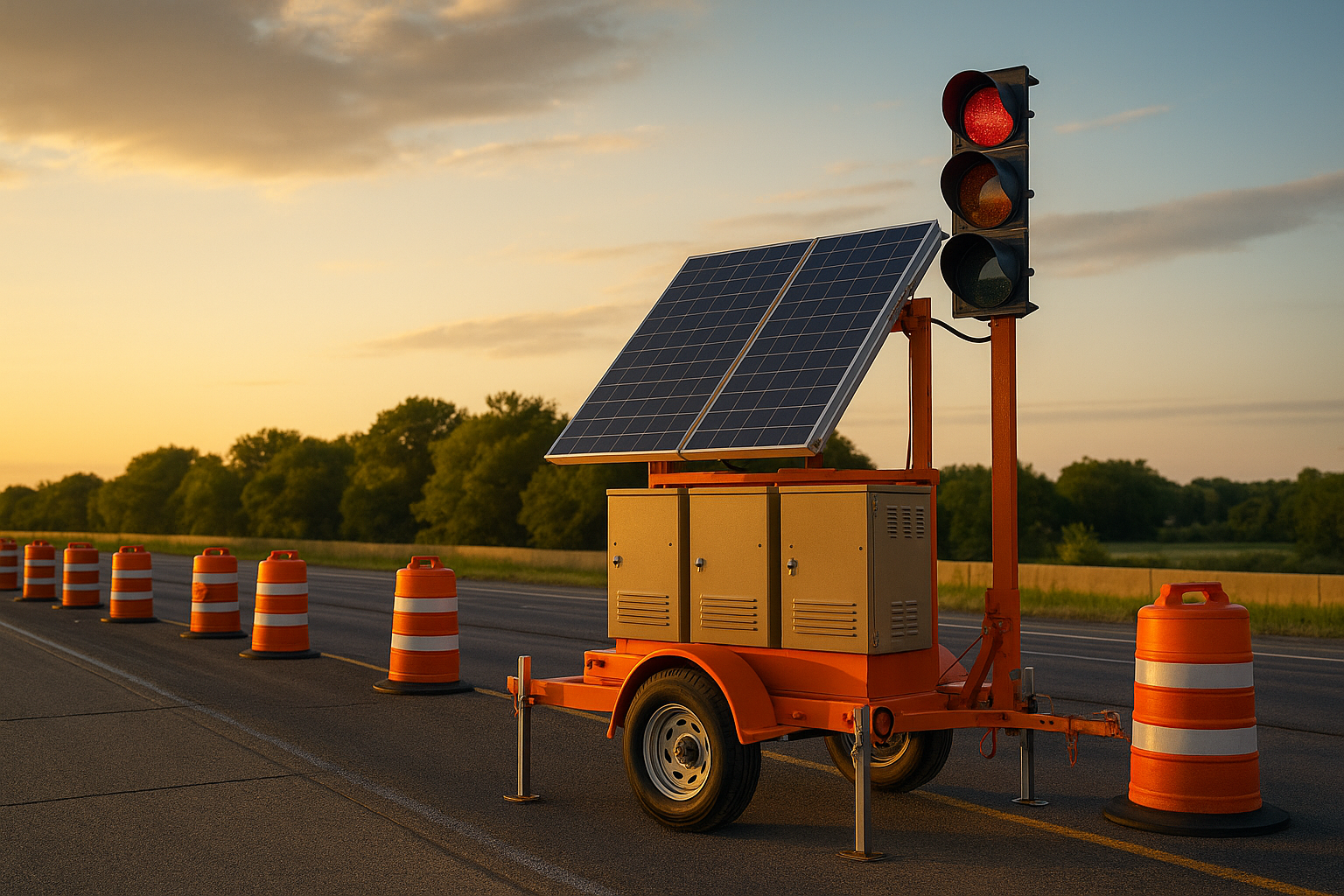

Rising energy costs, noise concerns, and sustainability goals are changing how agencies and contractors in Illinois power temporary traffic control. For years, the default answer was a diesel generator parked beside a trailer. Today, solar and battery platforms, often with remote monitoring, give project managers a different way to think about risk and operating costs over the whole life of the equipment. A recent JTI analysis comparing solar and generator powered portable signals showed that fuel and labor quickly become the dominant costs for generator setups, while solar systems remove fuel entirely and reduce site visits through telemetry [1].

Illinois is also pushing toward more renewable energy on state facilities. A technical and financial feasibility study prepared for the Illinois Department of Transportation concluded that solar projects on IDOT properties are both administratively and economically feasible when carefully sited and sized [11]. That state level direction makes it easier for districts, counties, and contractors to treat solar powered work zone devices as a natural extension of broader sustainability policy rather than a special project.

At the same time, guidance such as the 11th Edition of the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices reminds practitioners that a traffic control plan must support efficient construction and efficient resolution of incidents as well as safety [2]. When power platforms reduce outages, truck rolls, and complaints, they contribute directly to that efficiency.

Table of Contents

Key cost drivers in modern work zone power systems

When you compare different power options, most of the life cycle spend falls into a predictable set of buckets. JTI’s own cost comparison for traffic control equipment and several independent studies on renewable powered signals and lighting highlight the same pattern [1][4][5].

Key drivers include:

- Fuel and energy

- Daily labor for refueling and inspection

- Scheduled and unscheduled maintenance

- Downtime risk and traffic delay

- Noise and emissions, which affect public acceptance and in some cases funding eligibility

- Telemetry and monitoring, which can reduce surprise failures

A simplified view looks like this:

| Cost driver | Generator powered setup | Solar battery setup | Hybrid solar plus generator setup |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel and energy | Continuous diesel expense, exposed to price swings [1] | No fuel purchases, energy from sun and stored batteries [7] | Lower diesel use than generator only, some fuel needed [6] |

| Daily labor | Regular refueling, on site inspections [1] | Mostly remote checks, fewer truck rolls [1] | Some refueling plus solar checks |

| Maintenance | Filters, oil, engine parts, more moving components [1] | Fewer moving parts, long service intervals [1][5] | Moderate, depends on generator duty cycle |

| Downtime risk | Fuel outs and mechanical failures more likely [1] | Multi day autonomy and solar recovery reduce outages [1] | Better than generator only |

| Noise and emissions | Noticeable noise and tailpipe emissions [5][8] | Near silent, zero in use emissions [7][8][9] | Reduced but not eliminated emissions [6] |

Solar street lighting and solar powered message sign case studies show that even where capital costs are higher, removing the energy bill and cutting maintenance can swing the total cost of ownership in favor of solar over time [5][7][10].

How traffic control cost efficiency changes over the lifecycle

Cost comparisons that focus only on purchase price tend to miss where most of the money is actually spent. In work zone applications, equipment often runs for long hours in demanding environments, so small differences in hourly fuel burn or site visits compound quickly.

The JTI solar versus generator guide evaluated a simple scenario: two portable signals running 24 hours per day for 30 days [1]. Fuel for the generators, at half a gallon per hour per unit and a sample fuel price of 4.25 dollars per gallon, produced an energy bill of just over 3,000 dollars. Adding daily labor for refueling and inspection plus estimated maintenance pushed the generator operating cost for the month to more than 5,600 dollars. The comparable solar setup, with remote checks and a small maintenance allowance, came in at about 425 dollars for the same period, for illustrative savings of more than 5,000 dollars over a single 30 day project [1].

That pattern scales with deployment length and the number of units. Each added generator introduces more fuel, more labor, and more opportunities for breakdowns. A solar powered system introduces higher upfront spend but very modest operating costs. Similar conclusions show up in research on renewable powered traffic signals and solar street lighting, where analysts found that solar signal systems could pay for themselves in roughly seven years and then continue delivering avoided electricity costs for more than a decade of remaining panel life [4][15].

A simple way to keep the lifecycle view realistic is to organize costs into:

- Upfront purchase or rental

- Annual operating expense for each power platform

- Residual asset value and remaining useful life

An agency or contractor that already has multiple generator units in its fleet might not pivot all at once. Instead, they can model adding solar battery units first to the highest duration or most remote projects, where the savings from avoided refueling and callouts are largest.

Illustrative operating cost comparison for two portable signals, 30 day project, based on JTI assumptions [1]:

| Setup | Fuel cost | Labor cost | Maintenance | 30 day operating cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generator pair | 3,060 | 1,950 | 600 | 5,610 |

| Solar battery pair | 0 | 325 | 100 | 425 |

| Difference | 3,060 | 1,625 | 500 | 5,185 |

Where local conditions, labor rates, or duty cycles differ, you would substitute local numbers into the same structure. The key insight is that the cost gap is dominated by recurring energy and labor, not purchase price, for long running work.

Comparing solar battery, hybrid, and generator only platforms

Generator only power still has a place, particularly for very short deployments or shaded locations. However, several industry sources show that when devices run for weeks at a time, hybrid or solar dominated systems reduce both emissions and fuel bills. A recent analysis of solar hybrid generators for LED light towers on construction sites, for example, found that a hybrid tower could supply close to 70 percent of its annual energy from solar panels, cutting fuel use from thousands of liters per year to a small fraction of the diesel only case, with significantly lower emissions and longer runtimes between refills [6].

Solar powered variable message sign manufacturers report similar patterns. They highlight lower operating costs through the elimination of fuel purchases, reduced maintenance, and a more predictable cost structure that is insulated from diesel price swings [7]. Rental providers now promote solar message boards with zero in use emissions, self contained charging, and long run autonomy for road and event operations [8][9].

From a practical standpoint, most fleets in Illinois will use a mix of:

- Fully solar battery powered trailers for portable signals, message signs, and radar units.

- Hybrid systems where solar handles most of the load and a compact generator or fuel cell stands by for backup.

- Legacy generator only units reserved for specific corner cases.

The question then becomes where to prioritize solar and hybrid systems so that the additional capital goes where it returns the most benefit. High duty cycle projects, multi site programs, and remote locations with long drive times to refuel are natural candidates.

Sizing systems for Illinois work zones

Illinois specific conditions matter when you choose panel sizes and battery autonomy targets. Research on solar powered traffic lights developed through the University of Illinois emphasized the local climate envelope, including typical annual rainfall and the range of average monthly high and low temperatures, when specifying panel output and storage requirements [13].

The IDOT solar feasibility study likewise evaluated dozens of candidate sites by location, utility service, and energy potential before narrowing to a smaller set of sites where solar projects made the most technical and economic sense [11]. That screening mindset translates well to temporary traffic applications: some projects and corridors are excellent solar candidates; some may justify hybrid designs; a few may remain better served by generators.

For portable signals, message boards, and radar trailers, practical design questions include:

- How many hours per day will equipment run, and at what loads.

- What level of autonomy you require in days of operation without charging.

- Seasonal differences in solar resource and temperature.

- Panel tilt and placement, including shading from trees, structures, or overpasses.

- Whether you want integrated telemetry to report battery state of charge, tilt events, and location.

A simple sizing rule used by many vendors is to set battery capacity for multiple days of expected load, then choose panel wattage so that the system can recharge from a low state of charge to near full over a realistic sequence of sunny and cloudy days. Hybrid and grid assist options can further reduce risk in marginal conditions.

Building a business case for agencies and contractors

General research on renewable powered traffic signalization and agency level solar projects provides a helpful backdrop for project level decisions. A study of renewable powered traffic signals in European cities concluded that solar powered traffic lights were both economically and environmentally viable, especially once recent decreases in solar panel costs were taken into account [4]. The same study noted an 85 percent global decrease in the levelized cost of energy for utility scale solar over roughly a decade, driven by technology improvements and economies of scale [4].

For Illinois specifically, the IDOT feasibility work found that large solar projects on IDOT controlled land could be price competitive with conventional electricity when structured through power purchase agreements, and that an agency wide renewable strategy would likely use a mix of large anchor projects and smaller distributed sites [11].

At the work zone level, project teams can organize their business case around:

- Avoided fuel expenditure over the life of each solar or hybrid unit.

- Avoided labor for refueling trips and routine inspections.

- Reduced risk of downtime, complaints, and delays.

- Potential access to sustainability oriented funding or scoring advantages on competitive bids.

Studies of work zone intelligent transportation system deployments have reported benefit cost ratios greater than 2 to 1 when delay reductions during major projects were included, even before factoring in emissions and safety effects [16]. When solar powered platforms support those ITS deployments by improving uptime and reducing field maintenance, they support the same goal: more benefit per dollar over the life of the installation.

Implementation checklist for Illinois projects

To turn concepts into procurement language and field practice, it helps to follow a consistent checklist. Drawing on FHWA work zone ITS guidance, MUTCD principles, and JTI’s own specification checklist for solar powered traffic control equipment, a typical Illinois project team can work through the following steps [1][2][3].

- Define use cases

- Lane closures or full intersection control.

- Estimated hours of operation per day and expected duration.

- Whether work is urban, suburban, or rural.

- Decide where solar and hybrid platforms make the most difference

- Long duration, multi site, or high labor cost projects.

- Locations where noise and emissions are sensitive concerns.

- Set technical requirements

- Panel wattage and battery capacity, expressed as target days of autonomy.

- Telemetry features such as state of charge, location, and alerts.

- Expected operating temperature range and enclosure ratings.

- Clarify performance and compliance

- MUTCD compliance for display, visibility, and device type.

- Any state or district specific requirements.

- Capture lifecycle expectations in specifications

- Warranty terms and response times.

- Preventive maintenance schedule.

- Expected service life and criteria for refurbishment or replacement.

- Translate the above into bid or rental language

- Include power platform requirements so bidders can price comparable solutions.

- Request worked examples of operating costs under realistic duty cycles.

This approach keeps energy and life cycle questions from being an afterthought. Instead, they are part of the same structured decision process that agencies already use for device selection and traffic control plans.

Risk, resilience, and sustainability

Beyond pure cost, energy choices affect resilience and community impact. Solar powered message boards and signal trailers operate with zero in use emissions, which can matter for agencies with greenhouse gas reduction targets or for corridors near sensitive land uses [7][8][9][10]. Solar platforms also run quietly, which reduces complaints near homes, schools, and hospitals.

Battery storage provides a buffer during short periods of poor weather and can be paired with grid or generator backup for longer events. FHWA research on energy plus traffic signals that combine wind and solar generation illustrates how hybrid renewable systems can feed both traffic equipment and, in some cases, the wider grid [12].

For private contractors, resilience has a more immediate translation: fewer emergency callouts and lower risk of liquidated damages for service failures. When a unit can operate autonomously for several days and can alert staff in advance of low battery conditions, the chances of a surprise outage at a critical work zone drop significantly.

Key takeaways

- Fuel and daily labor dominate generator operating costs for long running work zones, while solar and battery platforms largely remove those recurring costs [1][5][7].

- Research on renewable powered traffic signals and lighting shows that higher upfront costs can be offset by years of avoided energy and maintenance spend [4][5][15].

- Illinois agencies already have a roadmap for solar adoption on state facilities, and similar thinking can guide work zone power decisions [11].

- Modeling scenarios by project duration, number of units, and local fuel and labor rates helps agencies and contractors target solar and hybrid platforms where they return the most benefit.

References

Core guidance and Illinois context

[1] “Cost Comparison Traffic Control: Solar vs. Generator (2025 Guide),” JTI John Thomas Inc., 2025.

[2] “Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, 11th Edition, Part 6: Temporary Traffic Control,” Federal Highway Administration, December 1, 2023 [PDF].

[3] B. Schroeder et al., “Work Zone Intelligent Transportation Systems: Technology Overview,” Federal Highway Administration, 2021 [PDF].

[4] Smart Energy Design Assistance Center, “Technical and Financial Feasibility Study for Installation of Solar Panels at IDOT-Owned Facilities,” Illinois Center for Transportation, 2021 [PDF].

Renewable powered traffic signals and lighting

[5] M. Vukovic et al., “Renewable Energy-Powered Traffic Signalization as a Step to Carbon-Neutral Cities,” Sustainability, 15(7), 6164, 2023.

[6] “Cost Comparison Case: Solar Street Lighting vs Traditional Street Lights,” Engo Planet, 2023.

[7] “Creating Productive Roadways: Energy-Plus Traffic Signal Concept,” Federal Highway Administration, FHWA-HRT-12-063, 2012.

Solar and hybrid equipment and trailers

[8] “Solar Hybrid Generator vs Diesel: LED Light Tower Cost and Emissions Comparison,” OPTRAFFIC, June 26, 2025.

[9] “Solar-Powered Variable Message Signs for Remote Applications,” OPTRAFFIC, October 8, 2025.

[10] “Message Board LED,” Sunbelt Rentals, product overview page, accessed December 2025.

[11] “Solar-Powered Digital Message Board Trailer, Full Size,” United Rentals, product overview page, accessed December 2025.

[12] “Solar-Powered Trailers: Eco-Friendly Solutions,” Power Up Connect, July 25, 2024.

Technical design and climate considerations

[13] “Solar-Powered Traffic Light Design Specification,” ECE 445 Senior Design, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, 2021 [PDF].

[14] “Solar-Powered Traffic Light: Power and Control Subsystems,” ECE 445 Senior Design, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, 2021 [PDF].

Benefit cost and smart work zone research

[15] P. Edara et al., “Effectiveness of Work Zone Intelligent Transportation Systems,” Missouri Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Administration, 2013 [PDF].

[16] T. Gates et al., “Improving the Effectiveness of Speed Feedback Trailers in Freeway Work Zones,” Institute for Transportation, Iowa State University, March 2024 [PDF].